E.Y.E.: Divine Cybermancy

The Aon Center, King Arthur: Legend of the Sword, No Man’s Sky, E.Y.E. Divine Cybermancy.

In the world of artistic endeavor, there are countless examples of ambition colliding with cold business reality. Streum On Studios’ E.Y.E: Divine Cybermancy seems to be one of these examples, but in a slightly different way. Unlike the breathtakingly expensive failures mentioned above, the only checks E.Y.E. can’t cash are its visionary ones. It simply attempts too much, often falling flat on its face. For this reason, It likely is not worth your time. However, oddly, it has been worth mine.

Is this because our times have different value? No that's not what I mean. I mean that E.Y.E. has so much to offer me, that despite the big problems it has, I've found much value in it. These big problems are likely to be too much for most players, however.

For me, writing about E.Y.E.: Divine Cybermancy is an intimidating prospect for a few reasons. First, this game is huge. The campaign spans several areas, usually urban or industrial type environments, each of which are very large and nonlinear, with multiple objectives to complete.

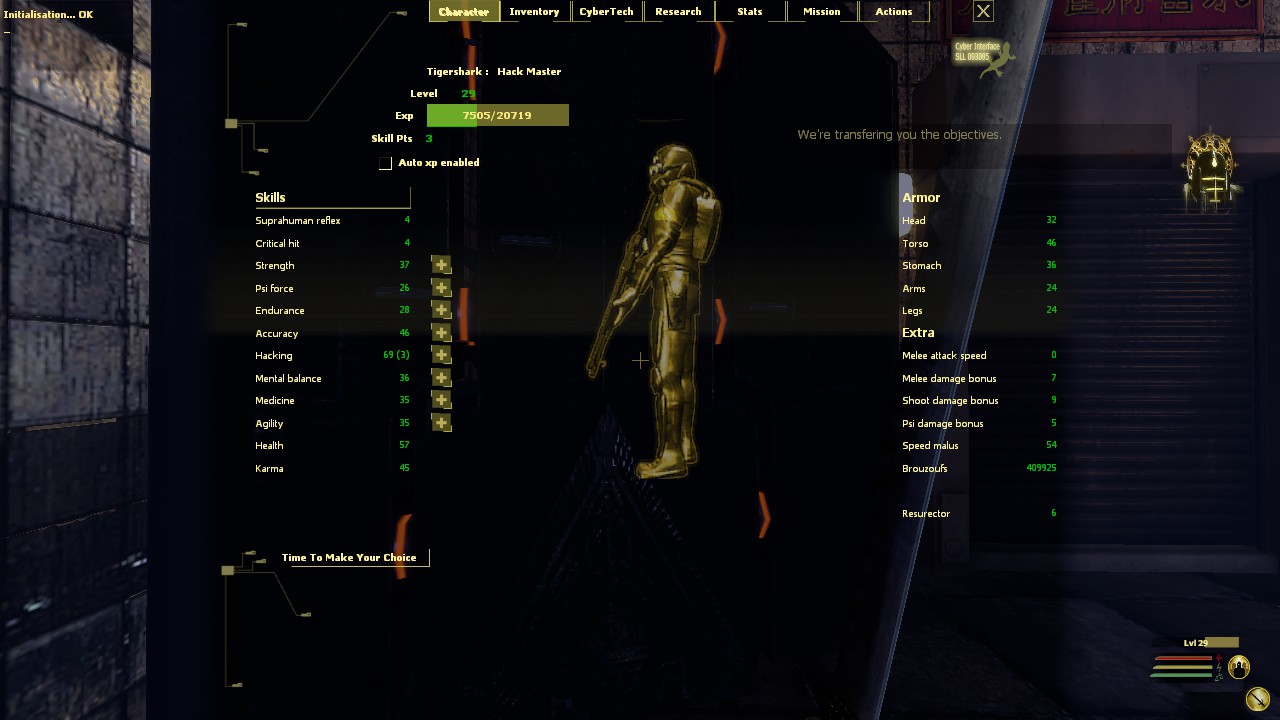

Second, the game is dense. It manages to put a lot of pathways and possibilities in all the maps. You'll hack, leap high and far, create clones of yourself, sling fireballs, sneak, and shoot. A lot.

Third, the plot seems to want to be an important part of the game, but it's borderline unintelligible. Streum On Studios is a French developer, and one can assume that the offensively poor dialog is just a shabby localization job; Reportedly it wasn't very good to begin with.

The final reason why it's tough to write about E.Y.E. is that, despite the fact that it is so difficult to recommend, I really love this game. Apart from being unintelligible it's also unstable, confusing, and it does a horrible job of teaching you its various systems. On the other hand, it is an infinitely fascinating, systems-filled FPS/RPG hybrid with astounding, though inconsistently executed, visual expression.

Somehow it manages to make so many head-scratching design decisions that you wonder if they're intentional. Even more puzzling is how it manages to hold together.

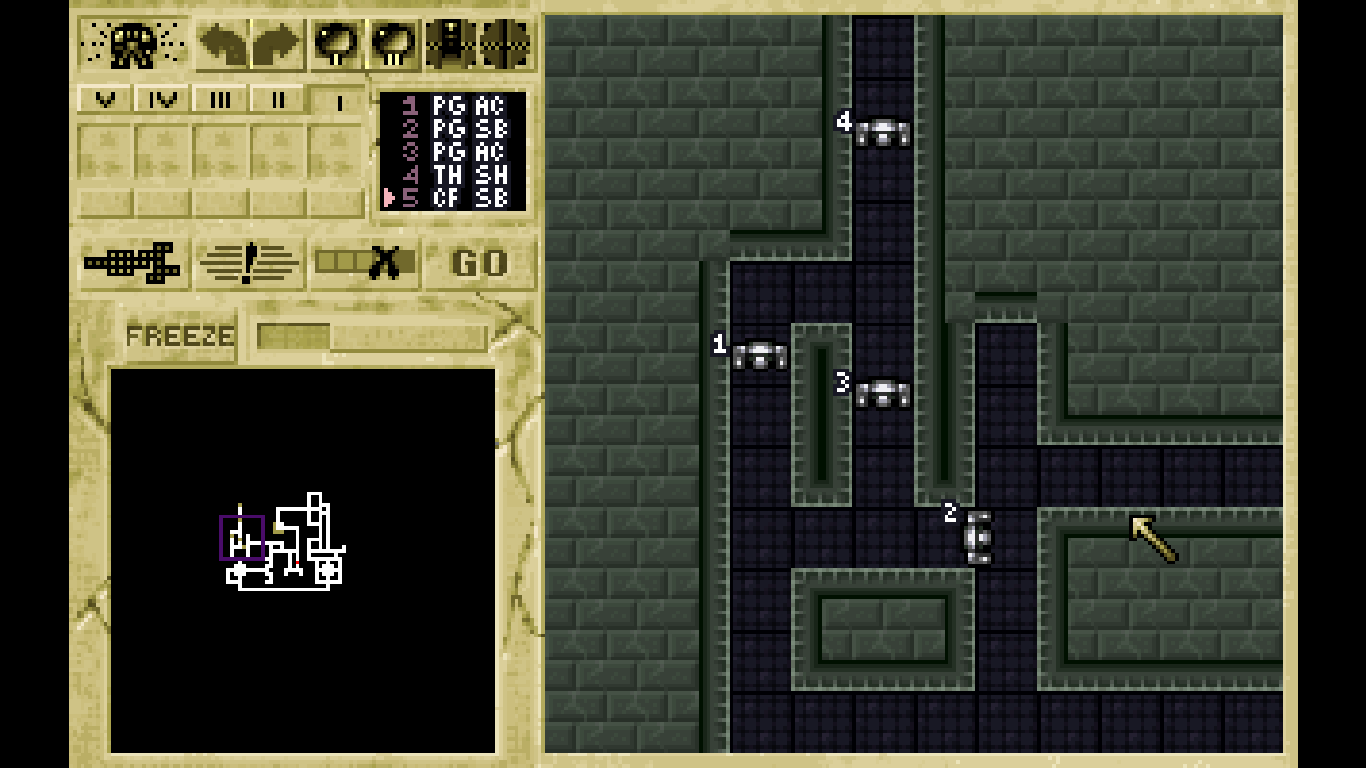

Of course, whether or not it holds together is up for debate. E.Y.E. is much more stable now than at release. However even now, the many systems do not always interact together in as satisfying a way as they would in Deus Ex or System Shock, clear inspirations for this game. In these foundational games, the systems line up such that you may solve all or most problems in many ways. Usually sneaking, hacking, or battling through the scenarios. In E.Y.E., You may sneak or hack, but the sneaking is almost completely ineffectual without using the cloaking power, and the hacking, though fun, is too time-consuming to use as a solution to a scenario. If you hack, it's usually to support yourself by turning a turret on your side or something similar.

This article is about the current version of the game. A major stumbling block for this game was how, at release, it was not only unstable, but poorly executed. For example, Stealth was impossible since enemies would see you from across the map through the fog, and ping you with pinpoint accuracy as they ran directly at you in single file. They were deadly, yet stupid. Now, although the enemy respawn rate is still obnoxious, and stealth, as mentioned, still won't work much without cloaking, enemy behavior is more believable while still putting up a stiff challenge. They'll even use some light squad tactics. Attempting to pin you down, flank you, or flush you out with grenades. It’s not perfect, but it's a much more satisfying experience.

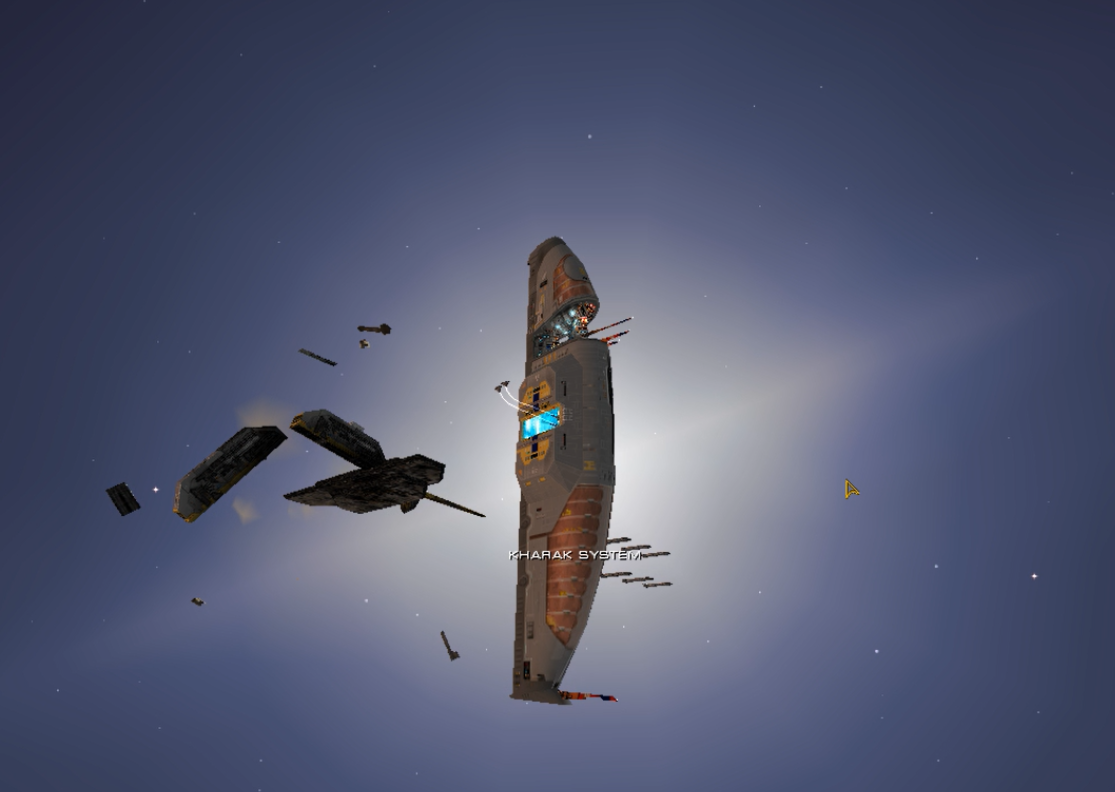

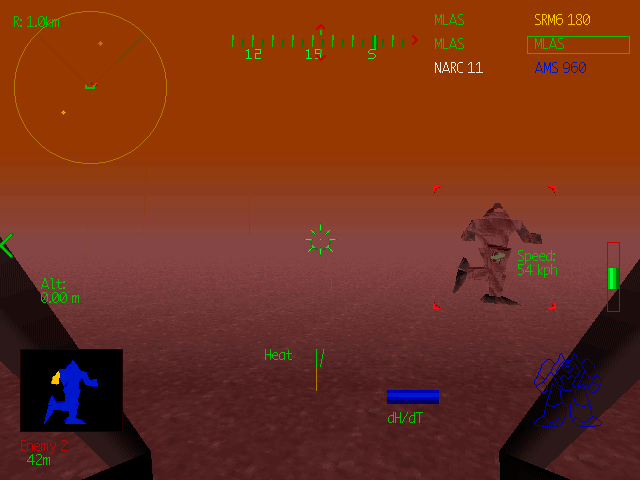

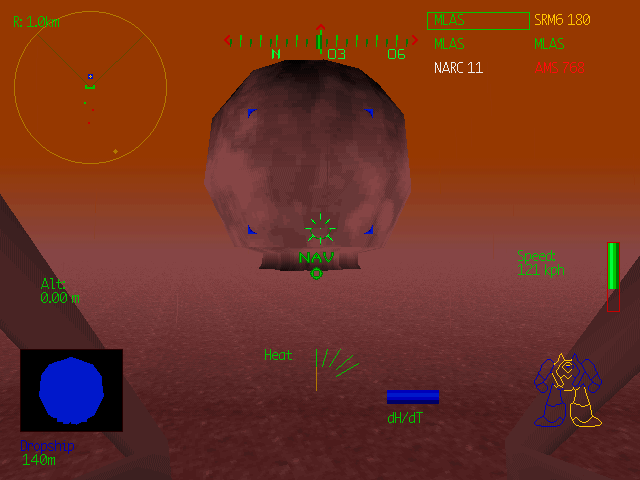

The setting of E.Y.E. is quite impressive. Apparently set hundreds of years in the future, it evokes a sort of crushingly oppressive post-post-post-apocalypse. At first, in any given environment, the only living creatures you tend to see are violent looters, trigger-happy Federal Police, and a couple varieties of creepy-crawly critters that pose you no harm (but can be victimized in the crossfire. Pro tip: avoid killing them)

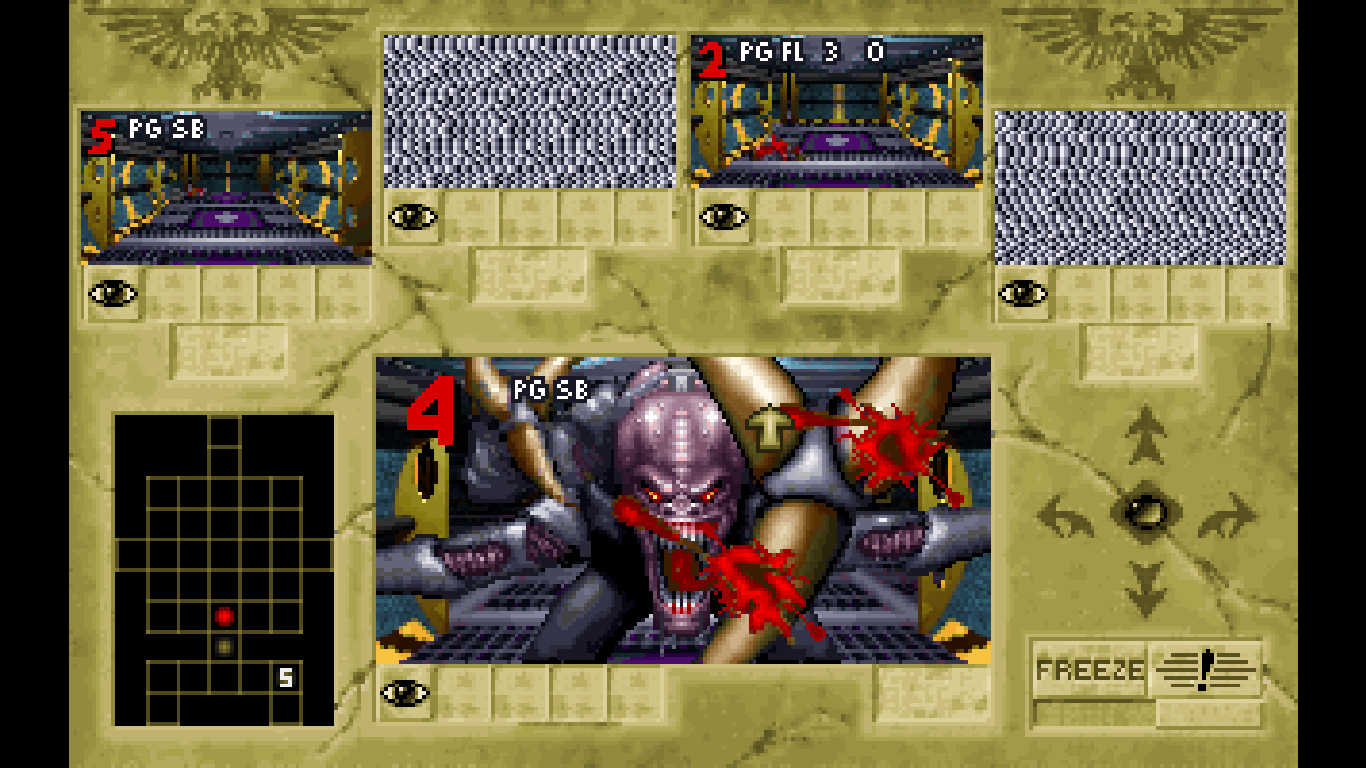

This world’s architecture is imposing and almost always incredible to look at. You'll see huge grungy dystopian skyscrapers and trashed housing projects laced with neon and impregnated with a polluted haze. The titular organization's HQ, which is referred to as a temple, is towering, its halls lined with large statues, its catwalks so high you can't see the bedrock below you, its walkways broken up with what one may assume are cyber-techno security checkpoints that flash green as you walk through them.

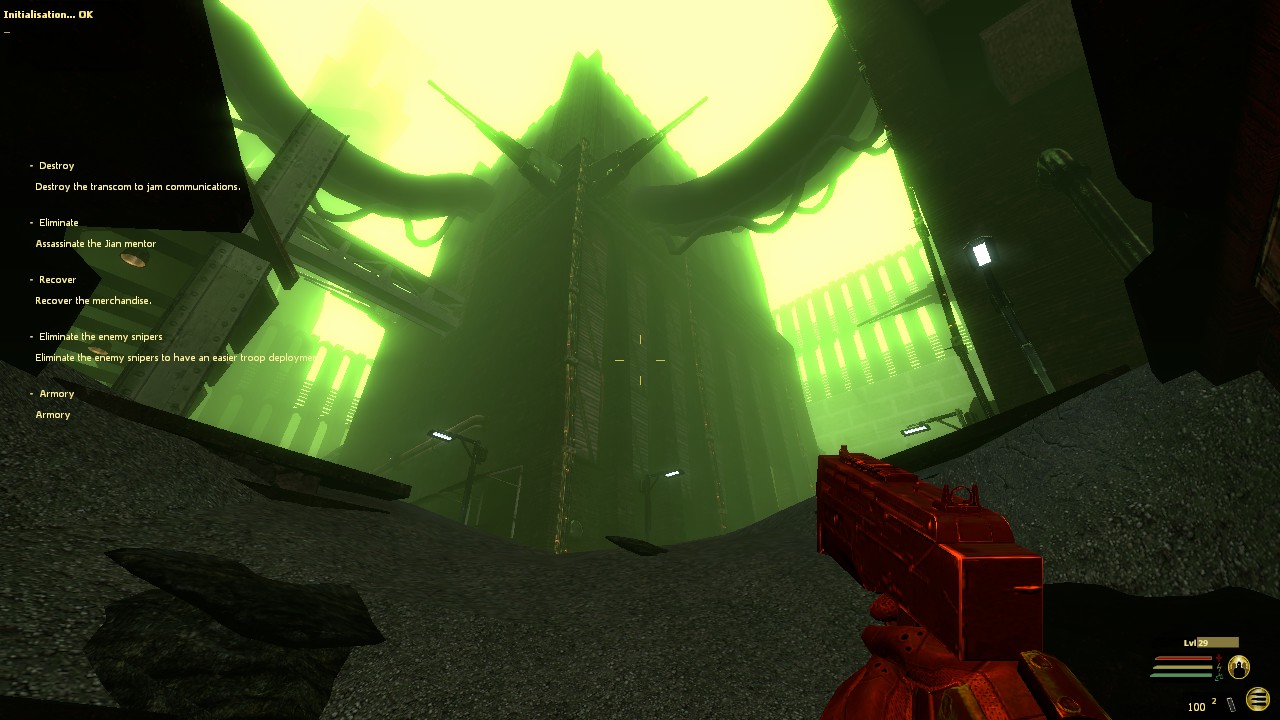

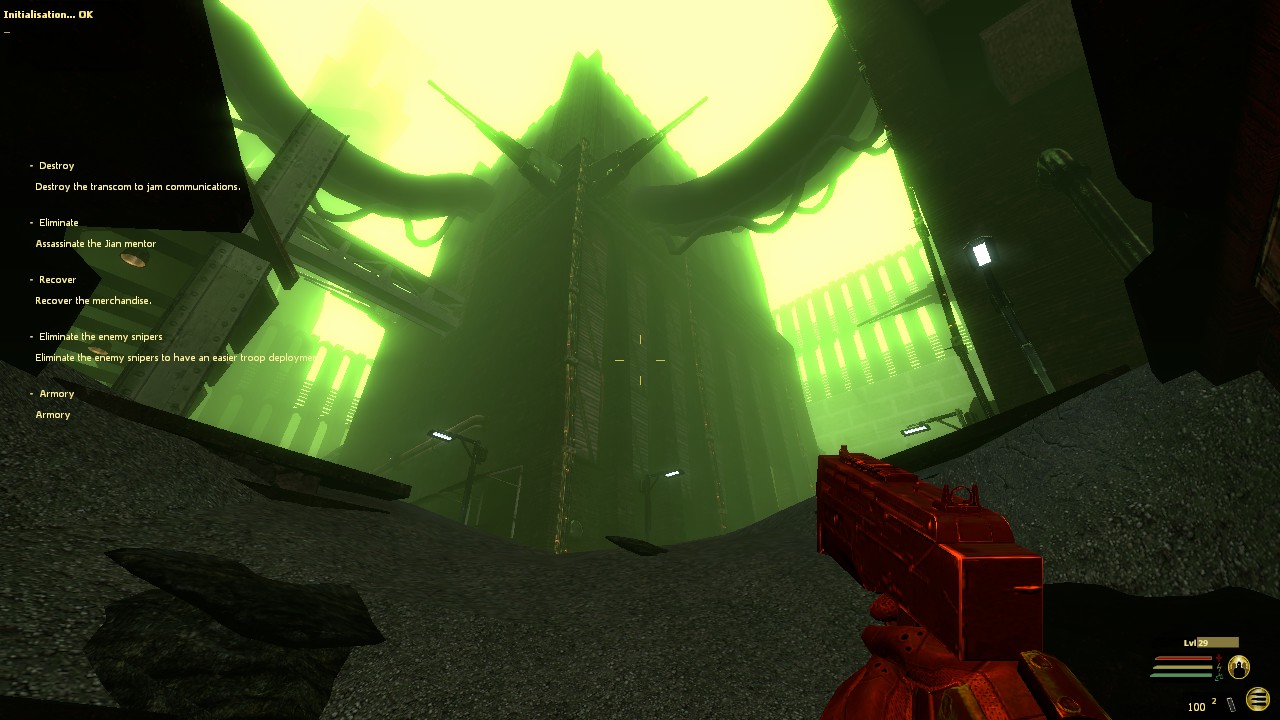

It's in a league of its own, even though there are a few hiccups in execution. For example, in an early mission, there is an otherworldly luminous green fog that hangs in the air, making it difficult to see distant enemies. It's like an artist's rendition of a tiny city inside a green neon light bulb. It's very odd, yet I choose to accept this as future cyber pollution.

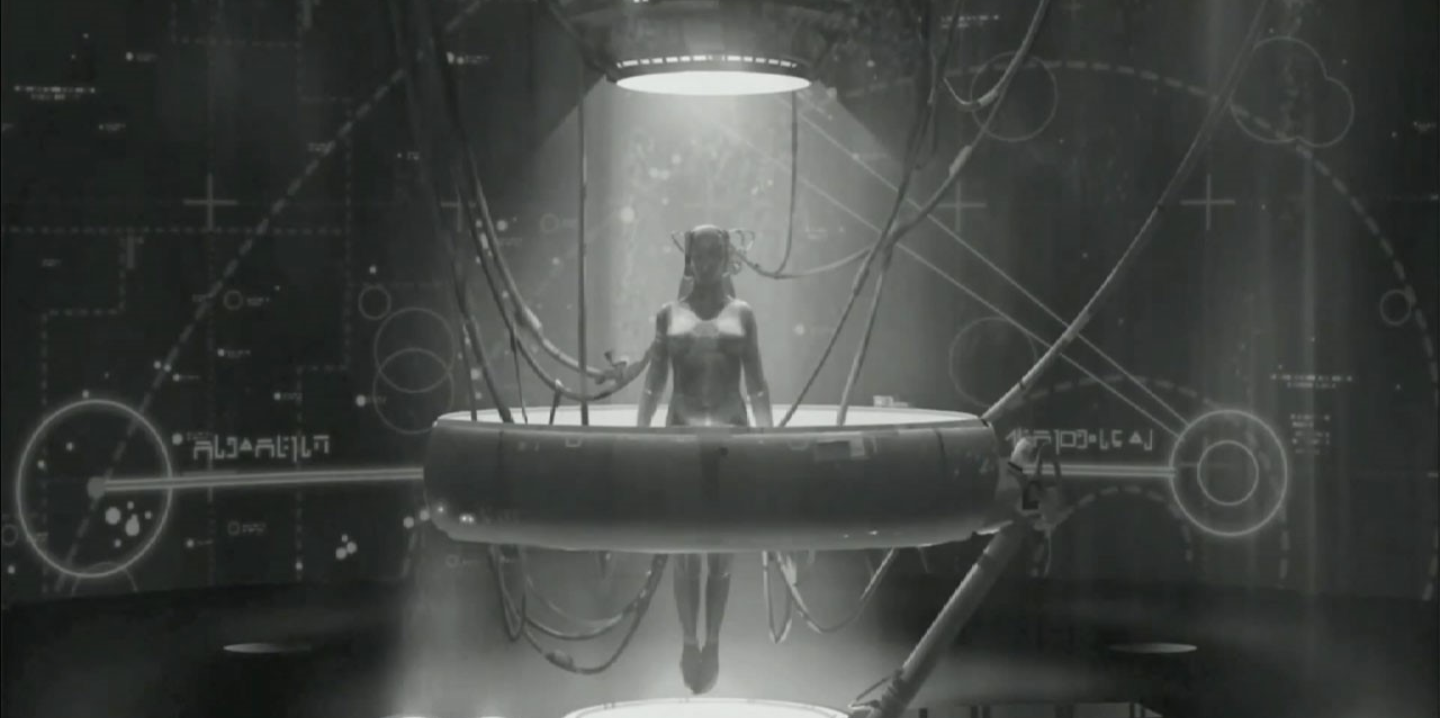

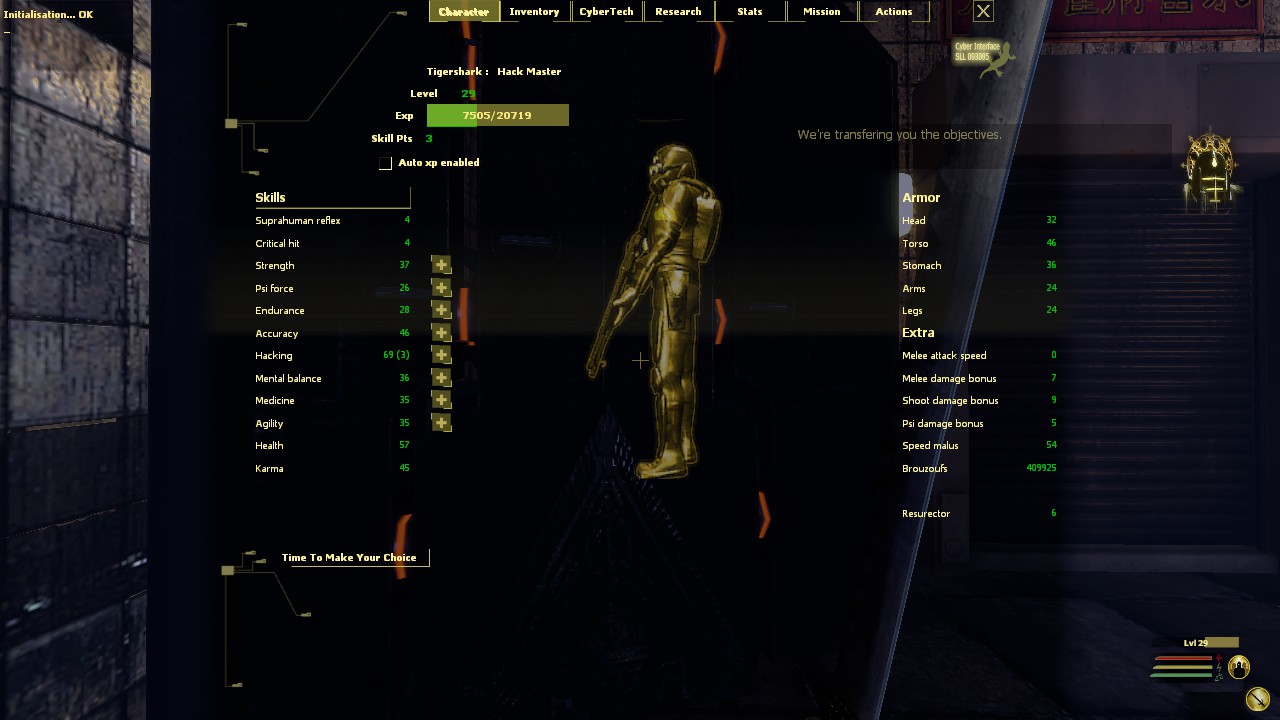

Without a doubt, the most striking element of the visual design is the character models. In the E.Y.E. organization, there are two secretly feuding factions. Your faction, called the Culter Dei, adorn themselves a sort of black Crusades-era armor that is full of decorative elements like gold trim, little lion heads, and even ornamental cyber halos. It's an eye-searing mix of medieval religious warrior and neon techno-soldier. Some evoke heavy metal album cover art with skull-shaped helmets.

The rival faction are the Jian. They share some of the same color palette in their fashion, that is, gold adornments on black armor, but draw a striking Asian silhouette. Many wear a beautiful conical douli brimmed with a rich gold trim, their cyber eyes glowing from underneath the hat’s shadow. Others have vaguely feudal Japanese Samurai style skirted helmets with a crescent tilted on its side which give the effect of golden bull’s horns. Both factions are beautiful and almost obnoxiously ornate in design.

The plot is confusing and poor, but I managed to barely get a sense of it.You are an agent of E.Y.E. which, as mentioned, is divided into two secretly warring factions: the Culter Dei, and the Jian. You awake with amnesia after failed mission and immediately scramble back to your HQ. Your commander wants to continue the campaign against the Jian, but your mentor wants peace, supposedly to unite against the Federation, which might be evil. There is also extra-dimensional force that is imposing itself onto the real world. This means monsters are bursting through portals and attacking anyone in their way.

So is E.Y.E. an Illuminati-esque string-pulling secret organization? Hard to say. What is their purpose or mission statement? Couldn’t tell you. Why do they send you on these missions? Because you’re available. What is does this extra-dimensional force have to do with anything? This isn't ever explained satisfactorily that I saw.

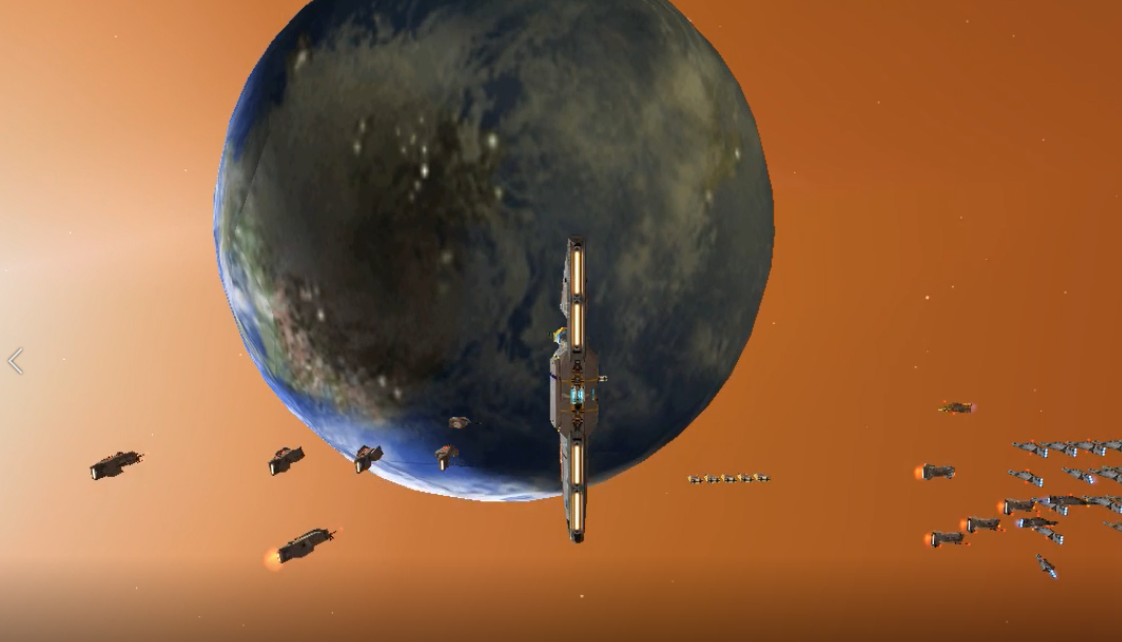

The hub of the game is the E.Y.E. headquarters, where you can purchase weapons, cybernetic upgrades, read up on the extensive history of the world in the archives, and of course, receive missions and launch them.

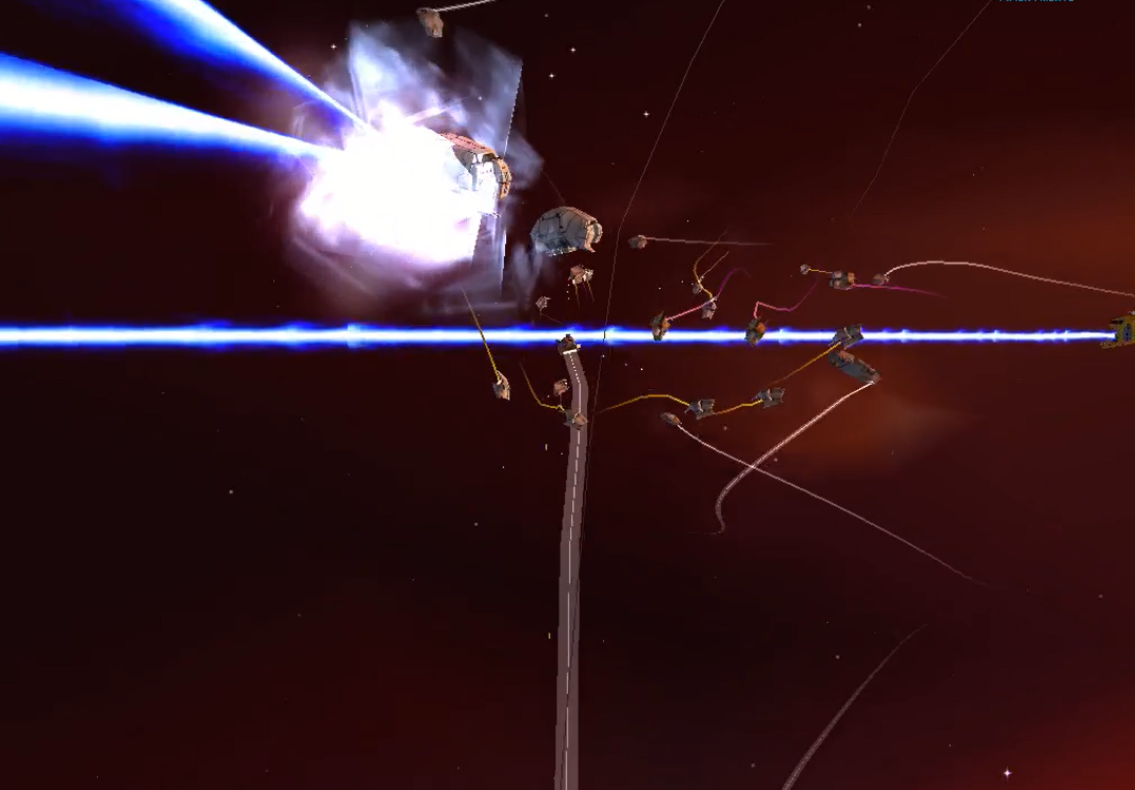

The first couple missions take place in cities, but not every mission area is urban, there are some vast outdoor environments that seem to defy what I thought the Source engine could do. Even if a few of them are pretty barren, they contain at least a couple interesting and intimidating landmarks. There are a few military base-looking structures, industrial complexes, and other sorts of areas too. These are always less impressive than the city environments, which feature stunning derelict tenements, under-city waterways, sewers, alleyways, catwalks et al. However, every map is sprawling, vertical, and multi-leveled, usually with multiple paths leading to any given area, each one rife with possibilities.

Except these possibilities usually mean mowing down a lot of people. The tools to do so are hit-and-miss. The 3-round burst medium-range assault rifle is useless, especially in the missions where the ethereal mutant monsters continuously pour in boringly from various spawn points on the map. On the other hand, the HS 010 is a Mac-10-esque machine pistol with a brain-rattling report and an absolutely blinding rate of fire. It features an alternate firing mode that doubles its already blistering firing rate. E.Y.E.’s HS 010 sets a watermark for video game submachine guns.

There are other rifles, submachine guns, shotguns, sniper rifles, pistols and melee weapons. They’re mostly fine. The Magnum “Bear Hunter” variety of pistols are fun, and the silenced semi-auto sniper rifle is quite useful. In a very nice touch, you can dual wield a pistol and a sword, either the default Katana or the mighty Damocles, which is useful for a gentleman Samurai-wizard player.

As mentioned, you’ll mostly shoot, but there are a couple other things you can do.

Depending on stats involving your psychic prowess, you can access the aforementioned extra-dimensional force to perform what amounts to magic. You can magically jump very high and far, shoot magical projectiles, create magical replicas of yourself to help in combat, and other tricks. If you choose this path, it's possible to become a very powerful cyber-wizard.

There is a bizarre research system in which you remotely assign scientists to investigate things, usually items and substances strangely dropped at random by fallen enemies. It takes real-world time, which can be adjusted based on how much money you want to invest in it. Sometimes the research will yield nothing. Usually it will unlock useful items and abilities.

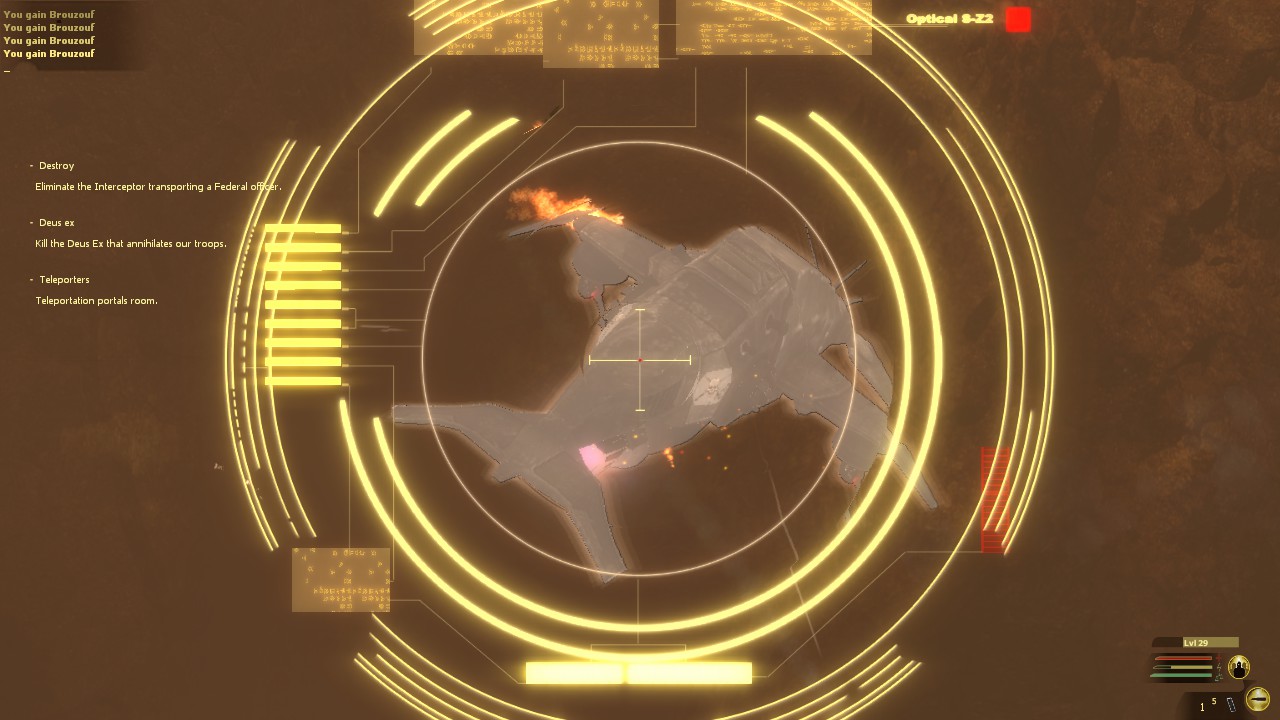

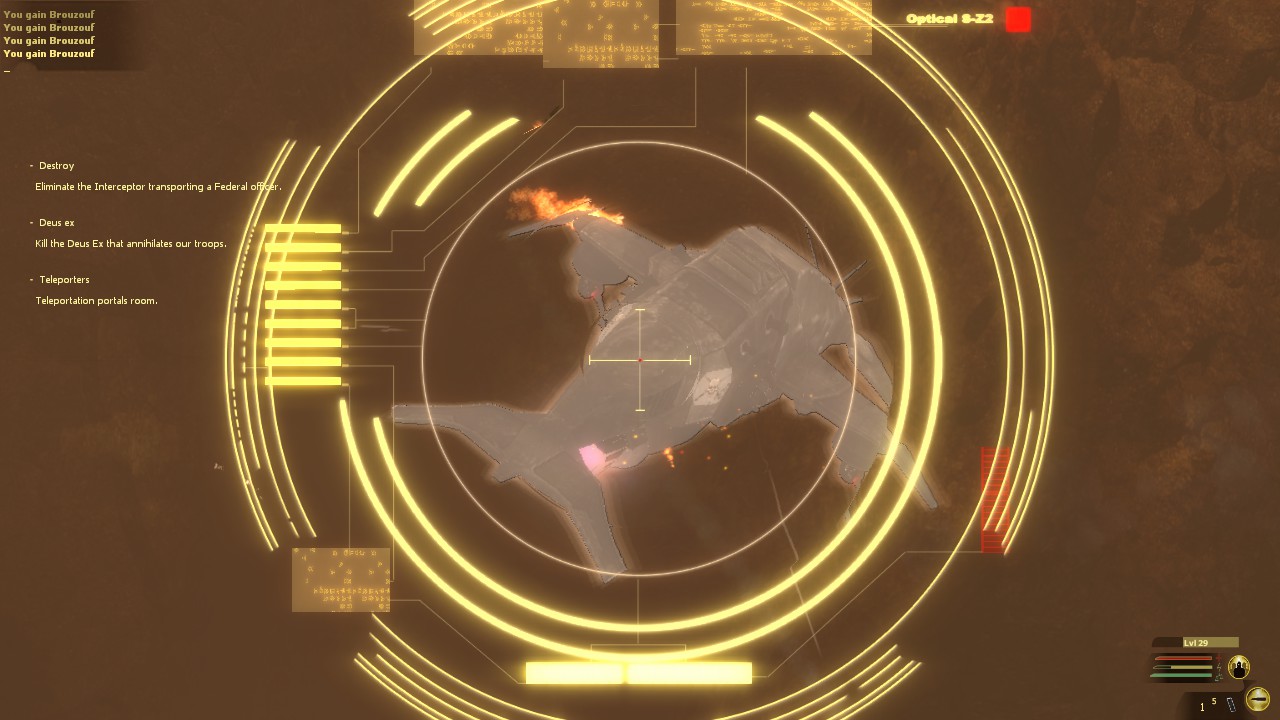

The best activity not involving shooting, however, is hacking. In E.Y.E., hacking is a menu-driven affair akin to a JRPG battle system. An overlay appears listing all hackable items in range. They can be ATMs, computers, turrets, or even people. Once the target is chosen, you see a menu listing five “viruses” which amount to an attack and various buffs for you and debuffs for the target. Also seen are your “cyber HP”, attack power, and defense power, as well as those of your target. Once you commence the hacking, the target will attempt to hack you back in self-defence. It is a thrilling and tense real-time chess match of buffs, debuffs, and choosing when it’s wise to attack. It’s made even more intense by the fact that the game will continue around you, so you may be seen and attacked in the middle of a hack. Luckily, this action can be easily cancelled.

If your opponent bests you in the hack, you may end up hacked yourself. Your vision will be shrouded in a purple haze and a giant smiley face with X’ed out eyes will taunt you. The only cure for this ailment is to open the hack menu again and hack yourself.

If you are successful, then many of the expected things happen. The turret now works for you, the locked door opens, etc. However the most fascinating thing happens if you hack a person. You can choose a few actions here. Some are expected like immediately destroying them or turning them to your side to fight alongside you, or you can do some less expected things like mind control.

This manifests in unexpected ways. You don’t directly control the victim, but you see their view in the UI overlay. There are five mouse-controlled buttons: Move forward, turn left and right, and target/fire weapon. The indirect way you control the target implies the digital, holding-on-by-a-thread manner in which you’ve taken over their faculties. It is a sick thrill to order your victim to walk right up to their captain, target them, and gun them down. Usually the screen will immediately cut to static as his startled companions eliminate the unexpected traitor.

The campaign has its fun moments by itself, but it gets rather wild when played in co-op. E.Y.E. has a rather unique claim to fame in its ability to accommodate up to 8 players in co-op in some game modes. Fascinatingly, the entire campaign can be played with up to 4 players.

Aside from campaign co-op, any of the maps can be loaded in solo or co-op, and mission objectives will be randomly generated. There are many objective types: such as hacking a terminal, placing a bomb, or assassinating a particular enemy. It is a surprisingly enjoyable way to repurpose your favorite campaign maps.

In fact, most of the enjoyment from E.Y.E.: Divine Cybermancy comes from doing this. Whether solo or in co-op, the random mission generator is surprisingly robust, and the map conditions are likewise randomized. If you’re unlucky, then the extra-dimensional monsters will flood the map, turning it into a painfully poor Left4Dead game. More likely, however, you'll get a better outcome, such as a VTOL gunship hovering overhead, searching for you, or a roving band of Jian elite shock troopers sweeping through the map, creating an interesting tension and challenge.

So is E.Y.E.: Divine Cybermancy worth your time? If the flaws bother you too much, then no. If you're only interested in story and characters, then definitely not. If, however, your looking for a unique and varied FPS experience in a striking world, lots of great shooting, and fun co-op, then E.Y.E. has a lot to offer.